How to Get Published

The world of publishing: a guide for writers

The agent

Most major publishers don’t accept manuscripts directly from writers, which means that to get your book published you will often need to get a literary agent as a key early step.

Literary agents take a cut of what you earn from your book in return for finding the right publisher for you, negotiating the best possible price and supporting your career development as a writer.

A day in the life of an agent

Niki Chang is a literary agent at The Good Literary Agency, a social enterprise which aims to discover, develop and launch the careers of writers of colour, or living with a disability, from a working-class background, who are LGBTQ+, or anyone who feels their story is not being told in the mainstream. Here, she reveals what a typical working day looks like.

9am Emails, emails, emails! Inevitably, so much of our business happens over email, so the first thing I do when I get in is check my emails. Urgent emails will be replied to at home before I leave for the office. We try to keep office hours for responding to emails unless it’s an emergency. Some days I will then switch off my email alerts and phone calls for the morning so that I can do an edit on a client's manuscript prior to submission, or read through submissions from writers looking for representation.

10am Meet with a prospective author. I will have read their work and would like to discuss it with them. This is also a chance for them to ask me about what I do and how we work as an agency. It’s also an opportunity to get to know each other as the agent-author relationship is a personal as well as a professional one. All being well, I will offer them representation and hopefully they will accept. We always encourage prospective authors to talk to other agents too before they make a decision.

11am We might have a quick agency meeting where we update each other with the latest news, what stage our authors are at with their manuscripts and what response we are getting to a book that is on submission. In the absence of an agency meeting, we are a very small, very collaborative and supportive team, so we are constantly chatting to each other throughout the day anyway, either in person or on Slack, a messaging app. We are greater than the sum of our parts and Slack functions as a sounding board where we can swap advice and ideas.

12pm Prepare a manuscript before submitting to editors for their consideration. This involves selecting which editors I want to send the manuscript to, writing a submission letter to the editor which will accompany the manuscript, and telling them a bit about the book and why it’s so brilliant. I usually call these editors to discuss the author and their work before sending over the manuscript via email.

1pm Meet an editor for lunch to catch up. We might discuss what’s going on in the industry, what books they’ve bought or published recently, what books I’ve sold recently. We might also discuss books they have tried to buy but which they lost to another publisher, as well as what books they would kill to publish. I will also ‘pitch’ them books I am going to send out soon so that they are on standby to receive them. We all work hard to maintain relationships across the industry. Editors receive dozens of submissions from agents every day, so if they are expecting yours, they will hopefully prioritize it.

2pm Phone call with an author, for a general catch-up, to talk about their work or to talk through something they are worried about. It’s my job either to reassure them what they are concerned about is normal, or to take action if it’s not. Likewise, I might call an editor to discuss a cover design that is not quite right, ask for sales figures for a book that’s been published, or look at publicity and marketing plans for a book that will be published soon.

3pm Sending out an author’s book to a select list of editors is like matchmaking – we are trying to find the best home for an author and their book. If it’s a good week, I’ll have at least one offer from a publisher to acquire an author’s book. If more than one publisher wants to acquire the book, the fairest way to decide is to hold an auction. I set the rules of the auction to make sure it’s a level playing field for the publishers. We might go in to meet the editor and their team to talk through their ideas and vision for how they will publish the book. As agent, it’s my duty to look after my author’s best interests and advise them accordingly, bringing my experience of the industry to the conversation as well as listening to what they want and what is important to them. Auction or not, I will negotiate the best deal possible with the editor.

4pm Coffee with a literary scout or our foreign rights team to discuss what the foreign markets are doing as well as plan submissions of our authors’ books to foreign publishers for translation.

4.30pm Discuss submissions with our assistant. At The Good Literary Agency we have an in-house development editor as well as freelance editors who may work on our authors’ manuscripts. And while our assistant is often the first person to read our submissions, we all look at the ones that are most promising so we can decide whether to offer representation, discuss what work we think might need to be done before we do or give the most constructive feedback we can.

5pm Review, negotiate and finalise contracts for the deals that have been agreed with publishers. This involves negotiating the best terms for our clients, answering any queries they might have on the contract and then getting them to sign on the dotted line! We keep an eye on the money to make sure our clients get paid as quickly as possible.

The thing about agenting is that every day is different. But a lot of our job takes place outside office hours and might include the following on any given evening ...

- Give a talk to aspiring writers, students who are studying creative writing, literary festivals etc.

- Judge a literary prize

- Attend a party held by a publisher. Authors, agents and all manner of people from the industry will be invited to attend. This is an opportunity to catch up with familiar faces, meet new people or even fangirl over a dream author, but they can also be tiring and take up your precious free time – they are also not obligatory.

- An author’s book launch. Budgets are smaller these days so most books are not celebrated with a launch per se – the editor, agent and author might go out for lunch or dinner – but they do still happen, usually in a bookshop.

- Try to read for pleasure when possible!

Dos and don'ts of approaching literary agents

The publisher

Our role as publisher is to work on your manuscript alongside you and your literary agent to make your book the best it can possibly be.

We then bring together experts from across our business, including design, sales, publicity and marketing, to connect your book with as many readers as possible around the world.

What editors are looking for

What if you’re writing for children or young adults?

Children’s books vary hugely from cloth and board books for our youngest readers, up to young adult fiction for teenagers. Here, three of the team from Penguin Random House Children’s talk about what they’re looking for.

Joe Marriott, Picture Book Commissioning Editor

I work with a team of designers and editors making picture books for babies and readers between 2 and 6, both stories and illustrated non-fiction. I’m looking for original texts and ideas (and illustrations) that are funny, clever, surprising or heart-warming. Key elements to think about are a clever or thought-provoking scenario, memorable characters and a structure that allows every page, and word, to count.

I usually know quickly whether I like something, but ultimately it must have broad appeal beyond just me – and be right for the mix on our specific picture book list. This involves discussions with many different areas of the business.

As an adult looking for ideas that will entertain children I need to tap into the part of me that loved books, stories and ideas as a child. I also think about what works when I read books to children – and what appeals to me as a grown-up; it’s important not to lose sight of the adult reader, who needs to enjoy reading and re-reading the book to their child.

Most important is the child’s reaction – it’s key that they are engaged and entertained, but there should always be something that makes them think, and opens a conversation – however silly or serious.

Millie Lean, Assistant Editor

Editors are looking for so many different things in middle-grade submissions (books for 8 to 11 year-olds, although the term ‘middle-grade’ can be used to encompass anything for ages 6- 13), but a combination of being fresh, full of heart, unique, and unputdownable with brilliant writing is a great place to start. Each editor has different tastes in genre, writing style and voice, but literary agents are great at knowing who the right person is for your manuscript.

It is always great to bear in mind which books are already doing well in the children’s market and why. You can do this as easily as going to a bookshop or looking at the Amazon bestseller pages. Do you notice any similarities between what you want to write, the top-selling titles and the books that the shop is promoting the most? Which titles would you place your story between on the shelf?

It is also important to define why your book is similar to but different from market comparisons. Make your story stand out and fill a gap in the market. Think about what you represent as an author, and if there is anything about the way that you view the world and what you really want to say which you could utilise to make your manuscript unique.

The next step is to test your work on real-life children! Think about whether each child picking it up would feel represented in your story. Make sure that if you want your book to be funny the humour is actually laugh-out-loud hilarious for kids. The most successful middle-grade stories, like the Diary of a Wimpy Kid series or Roald Dahl’s books, are fabulously entertaining and accessible for kids (and parents love them because their child loves reading them)!

Children’s books have the power to shape a young person’s understanding of the world and help them develop a love of reading which can stay with them for the rest of their life. Publishers want kids to love our books, for reading to be fun, and for all children to be able to see themselves in the books we publish.

Carmen McCullough, Commissioning Editor

What I look for in a young adult book can vary quite a lot depending on what stories are resonating with the current young-adult audience. Most importantly though, I look for strong immersive writing – voice-led stories with distinctive characters that you feel invested in from the very first page. I also feel strongly that every child or young adult should be able to see themselves in a book, so I am particularly keen to publish diverse stories that reflect the world we live in.

Liking a book is instinctive, and if you feel a genuine passion for it, then it’s highly likely that it is publishable as there will be other readers who feel as strongly as you do. The question you then ask is how you would position the book in the market and whether it would be for a very broad audience or a more limited one because of the type of story that it is. A great story is a great story whether it’s aimed at children or at adults.

As a children’s book editor, I’m always interested in what is appealing to children or young adults at the moment (whether that’s books, films, games), but ultimately if you have a brilliant story then you feel confident that readers will enjoy it.

More than anything, I want readers to enjoy the books we publish – whether a story is funny or sad, dark or uplifting, I want them to feel that they were able to really engage with the story and characters and that the experience encourages them to keep reading.

The acquisition meeting

The key moment a publisher decides which books to ‘acquire’

Publishers regularly have ‘acquisition meetings’, which is when new manuscripts for possible publication are discussed. This meeting involves people from a variety of departments who all give their input as to whether a book should be acquired, or bought for publication. Here, the team from our publishing house Cornerstone explain some of the factors which affect their decision making.

The Managing Director: Susan Sandon

As chair of our weekly acquisitions meeting I try to ensure that an editor is given the time and space to pitch their project and that the ensuing discussion gives all the meeting’s participants a chance to express their view. I’m always interested in how passionate the acquiring editor is: it’s hard to make a success of a book you don’t wholeheartedly believe in – inspiring and rallying the team are such key parts of the publisher’s role. Much of what I am looking for crosses over with other attendees at the meeting: is there a market for the book, how big is it, do we have a clear view of how we might target the audience, should we be trying to acquire world rights in it, what format ought it to be, what price could it take and when might we publish?

Because our publishing house, Cornerstone, is made up of individual imprints with different editors acquiring for each imprint, it’s also my job to join the dots and think about how the book fits into our overall Cornerstone list. This is so that we don’t, for example, have a glut of first novels all publishing at the same time.

I will also be thinking about workloads: have we enough room to take the book on or does it need to be published at a point when sales, marketing and publicity already have their hands full? Is the editor being realistic about the work they will need to do with the author and have they the space to take it on among their other projects?

Before the book is acquired I will also appraise the project financially together with our Head of Commercial Affairs, determining whether it meets our financial criteria and what level we might set the advance at.

The editor: Tom Avery, Editorial Director at William Heinemann

For editors, the acquisitions meeting is a chance to present the new titles we would like to publish to our colleagues. It is the biggest step in what can be a long process, starting with speaking to an agent or writer or receiving a submission, and ending (hopefully) with the acquisition of the project. In between there are many stages, from imprint editorial meetings to extensive research, to conversations with colleagues across the company. The acquisitions meeting is the key moment when we decide, collectively, if we are going to pursue a project.

My job at the acquisitions meeting is to communicate three connected things to my colleagues.

Firstly, my passion. There is no better feeling than reading a submission and falling in love with it, and knowing how you will be able to publish it successfully. I try to spend a bit of time in each presentation describing and explaining not only why I care so much about the project, but why I think everyone will.

Following this is the question of why I think the project I am raising is worth us pursuing, taking into consideration its subject and approach, the author’s profile and publishing history, and where it sits in the market and what gap it might fill (including a mention of any suitable comparable titles).

Lastly, I have to clearly set out my vision for how we would publish the project, including publication date, format (size and shape), price, and, more broadly, how we would get it into the hands of as many people as possible.

The sales rep: Claire Simmonds, Sales Manager

In the acquisition meeting, my role is to identify the sales potential of a proposal. This involves identifying what retailers I think the book will sell through, across all formats, and to what level. My team’s job is to flag the opportunities a book presents in regards to our retailers and the potential challenges that could arise. Initially, I decide this through analysing the current market and trends, and where I see the proposal sitting within this.

The acquisitions meeting is, then, a great forum to discuss the editorial, publicity and marketing vision for the proposal, which further helps us determine the overall sales potential. We discuss what publication date, format and RRP (recommended retail price) we think will give the book the best chance of getting into the hands of as many people as possible. Once we have determined if we want to pitch for a book, sales then provide our sales forecast, which needs to be a fine balance between being both realistic and ambitious.

No two books are ever the same and so the meeting is always full of fresh discussions and brilliant energy.

The publicist: Charlotte Bush, Director of Publicity and Media Relations

My role is to look for the publicity potential in a book and give feedback on what the media opportunities might be.

For a non-fiction book I’m looking for media hooks – is there a special date this book would launch on or is it a particularly timely idea? Has the author had exclusive access, or do they show special expertise and/or originality?

For fiction the approach is slightly different: perhaps the author has an interesting backstory that they would be willing to talk about, or there may be a connection between the novel or its’ characters and a real-life story. And if the author is already in the public eye I will look into previous interviews and their social media profile too.

I’ll also involve other members of my team: they may have more expertise in certain areas or be closer to a current trend. At this stage it is all about putting yourself into the shoes of a journalist and sometimes playing devil’s advocate!

The marketer: Rebecca Ikin, Marketing Director

The marketing team will read and review every title ahead of the weekly acquisitions meeting. Marketing are involved at this early stage to help identify the book’s potential target market – who the book is for and how will we go about reaching them. We also consider how efficiently we can promote the book and what marketing budget we will need for the project.

We help the meeting understand the audience (who the book is for), positioning (the hook of the book and what will capture imaginations or help set it apart) and platform (market trends and demand or the individual’s profile).

At Penguin Random House we use audience segmentation and also run desk research, using tools like social media listening software or YouGov consumer data – particularly for non-fiction where we might be considering a new idea or a personality with a public profile.

We hope to blend that data and research with our collective and varied experience and instincts (built up over many years) with, of course, a more immediate response to the book and the writing. After all, you still want to be blown away by what’s on the page, and when that happens it’s incredible; the whole meeting is energized. It’s still the most exciting thing for us all, a real privilege in fact.

When lots of other publishing houses also have that same reaction, then an auction can get very heated. In those situations, marketing will work really closely with editorial and also very quickly (sometimes over just 24 hours) to pitch for the book to the author and agent. In those cases we are outlining (writing and designing) our entire publishing vision and promotional strategy for the book and hoping that our ambition and passion for it helps us win the book. It’s intense but can be hugely rewarding if your highly concentrated efforts pay off!

Jargon buster

Returns, rights, royalties. Synopsis, slush pile, subsidiary rights.

At times, it can seem like the words used by the world of publishing are just nonsense sounds, there to deliberately confuse you or make it harder for you to get a foot in the door.

But, while publishing has its own language, it's not as impenetrable as you might think. To help, we've compiled a handy jargon buster which gives you clear definitions of all the terms you need to know as a writer. You'll soon know the difference between an ARC and a proof (hint: there is none) and publishing will be a puzzle no more.

What does an editor do?

Ask the editors: dealing with feedback

Getting feedback from an editor for the first time can be a daunting process. Here, four editors answer some common queries from writers.

My editor’s just sent me the first letter about my book, and it’s so long. Does this mean my book is awful?

Simon Prosser, Publishing Director at Hamish Hamilton: Not at all. It may mean the book is terrific – but could be even better still. Perhaps the plot is complex and needs fine-tuning; perhaps there is a compelling character who could be given more space; perhaps there are unconscious repetitions of phrase or idea which need cutting or replacing; perhaps there is a tendency to say too much, when condensing would give the writing more strength.

An editor’s job at this stage is to be the writer’s ideal reader: which is to read with the utmost sympathy and understanding of what the writer is trying to achieve, while at the same time maintaining as objective an eye as possible, remaining alert to any ways in which the work can be improved. Even the simplest novel is a complex structure, with many moveable parts. And even a novel composed of individually perfect sentences may be imperfect – but, with luck, perfectible.

I thought the editor bought my book because they thought it was great. Why am I getting feedback?

Joel Richardson, crime and thriller Publisher at Penguin: Firstly, they did buy the book because they thought it was great! Editors are incredibly selective, so the fact that they’ve acquired your book means they think it’s something special.

That said, unless you’re the first person ever to write the perfect book (if so, congratulations!), the next stage is making sure it’s as good as it can be before it publishes. You’ve been working on the manuscript for an awfully long time, and so it’s nearly impossible for you to appraise it with fresh eyes. Do your characters come across the way you want them to? Will your twist ending successfully take readers by surprise? Those are questions only a new reader can answer.

In that sense, if an edit wasn’t focused on what could be improved, then it’s not really doing its job. Trust your editor to share your goal of making a great book even better, and look at everything they say with an open mind – and ask questions yourself if you don’t understand something, or don’t agree. There might still be hard work to go, but it will be worth it when you finally finish, and know that you left no stone unturned in making your book brilliant.

My editor’s asked me to change something I really love. Do I have to change it?

Andrea Henry, Editorial Director at Transworld: The work of a good editor can make all the difference, so listening carefully to what your editor has to say can be crucial to a book’s success. When you’ve perhaps spent years writing, investing time, energy and emotion, it becomes your baby and you feel protective of it. But it can become hard to see the wood for the trees. Your editor is reading with fresh eyes – seeing things more clearly than you might now be able to.

You might not always like what they’ve got to say and the edit can feel like a nit-picky process, in which your hard work is scrutinized and found lacking. If they’re trying to change something you love, be open to the conversation. You can push back and argue the toss, arrive at a compromise, or indeed reject suggestions that you feel really strongly about. But you’ll need to be able to justify your decision. The key thing is always to take your editor’s thoughts seriously. Keep in mind that, despite finding flaws, they loved your book enough to want to publish it. It’s their baby too now, and they’re there to help make your book the best it can be.

I’ve got so much to do and I’m not sure I’m going to get it done by the deadline. What should I do?

Ruth Knowles, Publisher at Puffin: Talk to us: we’re here to be your partner in this process, to help you make your book the very best it can be - and you absolutely don’t need to carry this worry alone. It’s always better to over-communicate rather than just stay silent, and it’s extremely likely that there’s some more time in any deadline to be found. Talking to your editor can help you unpick what’s causing the writing to feel hard or not right to you as well, and we’re so proud to be publishing you and working with you we’ll be delighted to be involved in even the most tricky bit of the process, I promise.

It can be good to take a break from struggling over the same section of the book too. Maybe try writing a couple of pages from a different character’s perspective or jump to a scene later in the book. It can free you up creatively and energise you for coming back to a section you’d previously found tricky.

The book

The moment you've been waiting for - holding your published book in your hands - is a special one for writer, agent and publisher. It's likely that your book will also be published as an ebook and audio book.

While it varies hugely how quickly a book is published, for many debut authors it can take around a year from when your book is acquired to publication day - allowing us to build a buzz around you and your book ahead of the big day.

Designing a cover

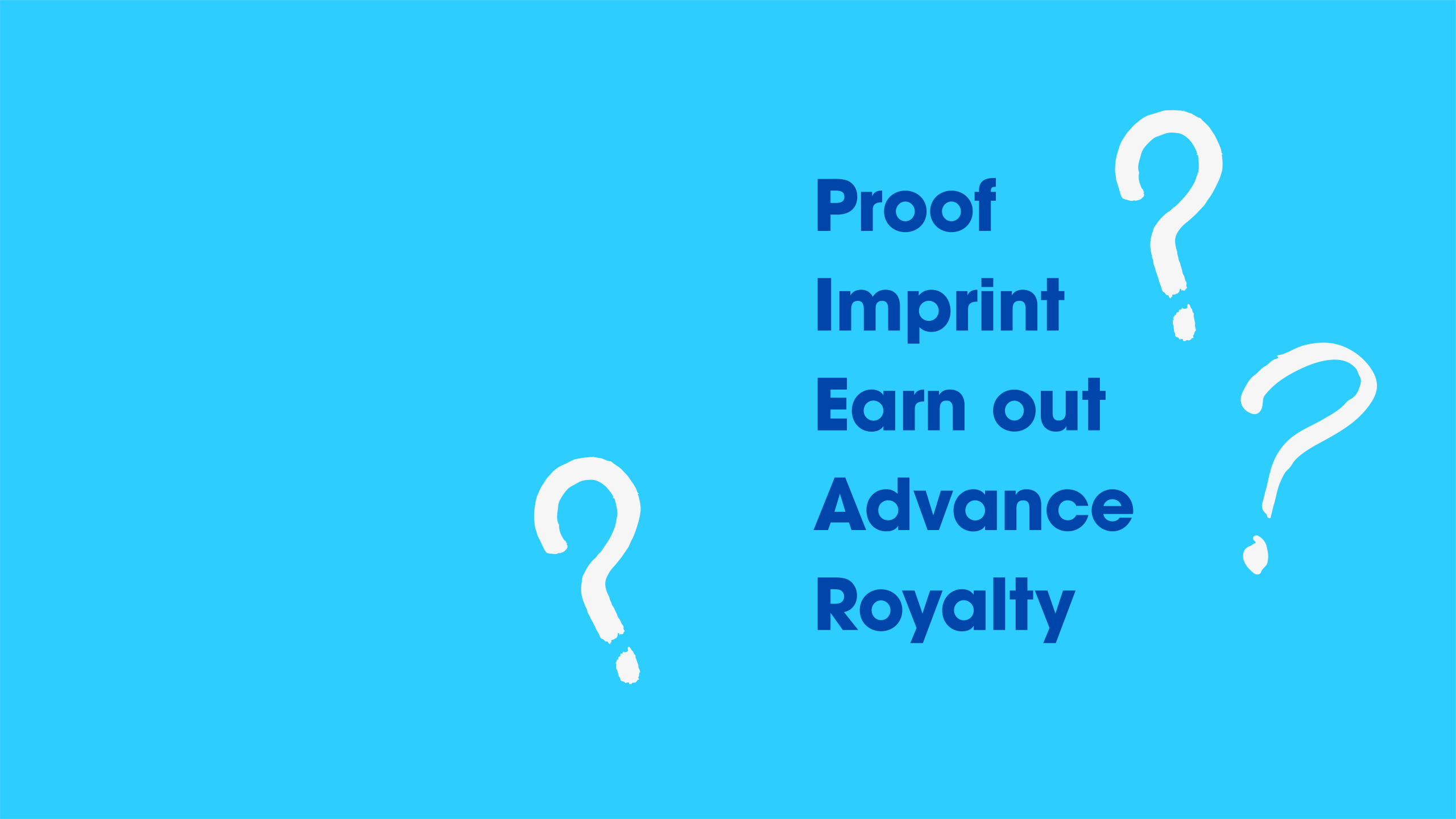

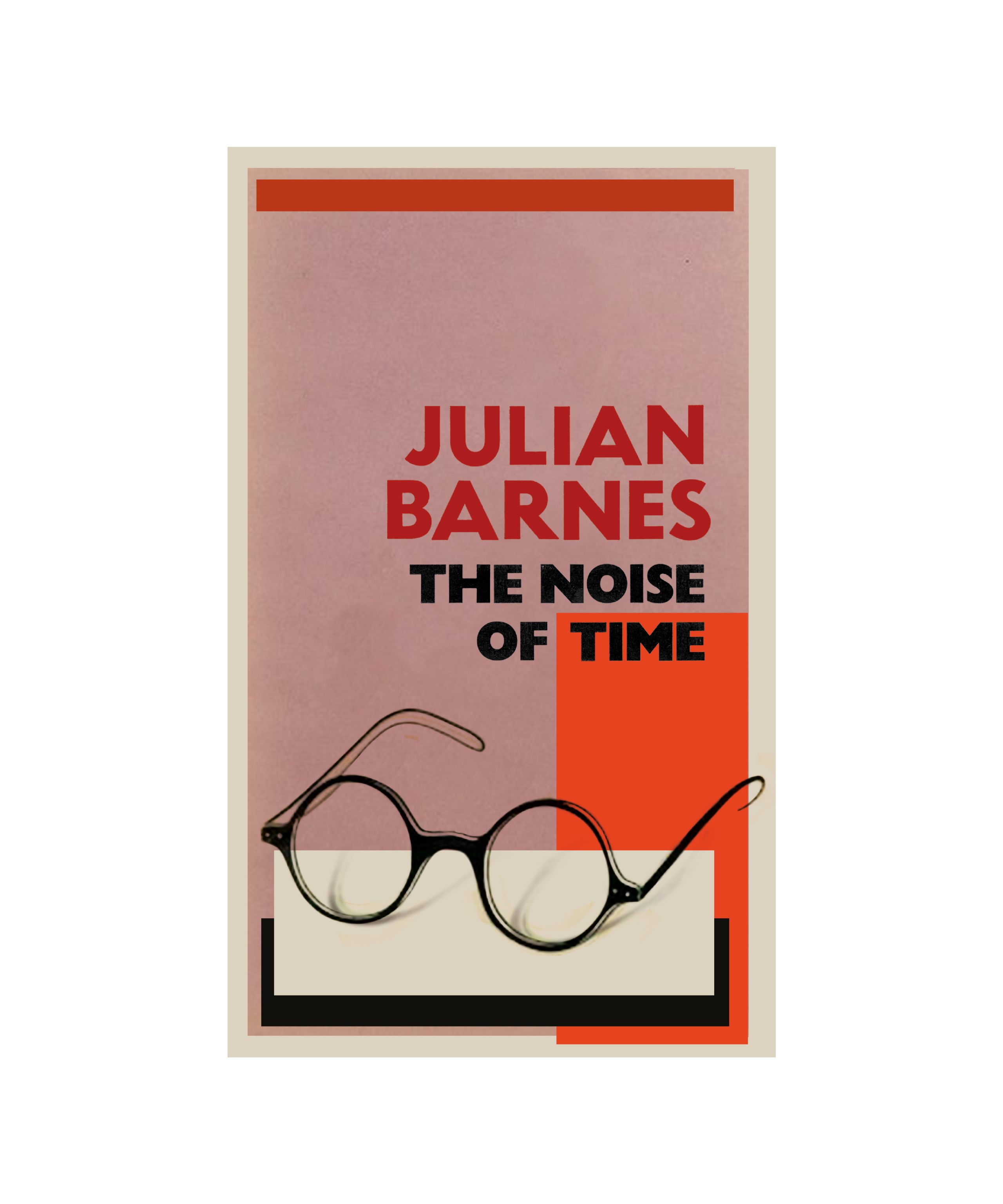

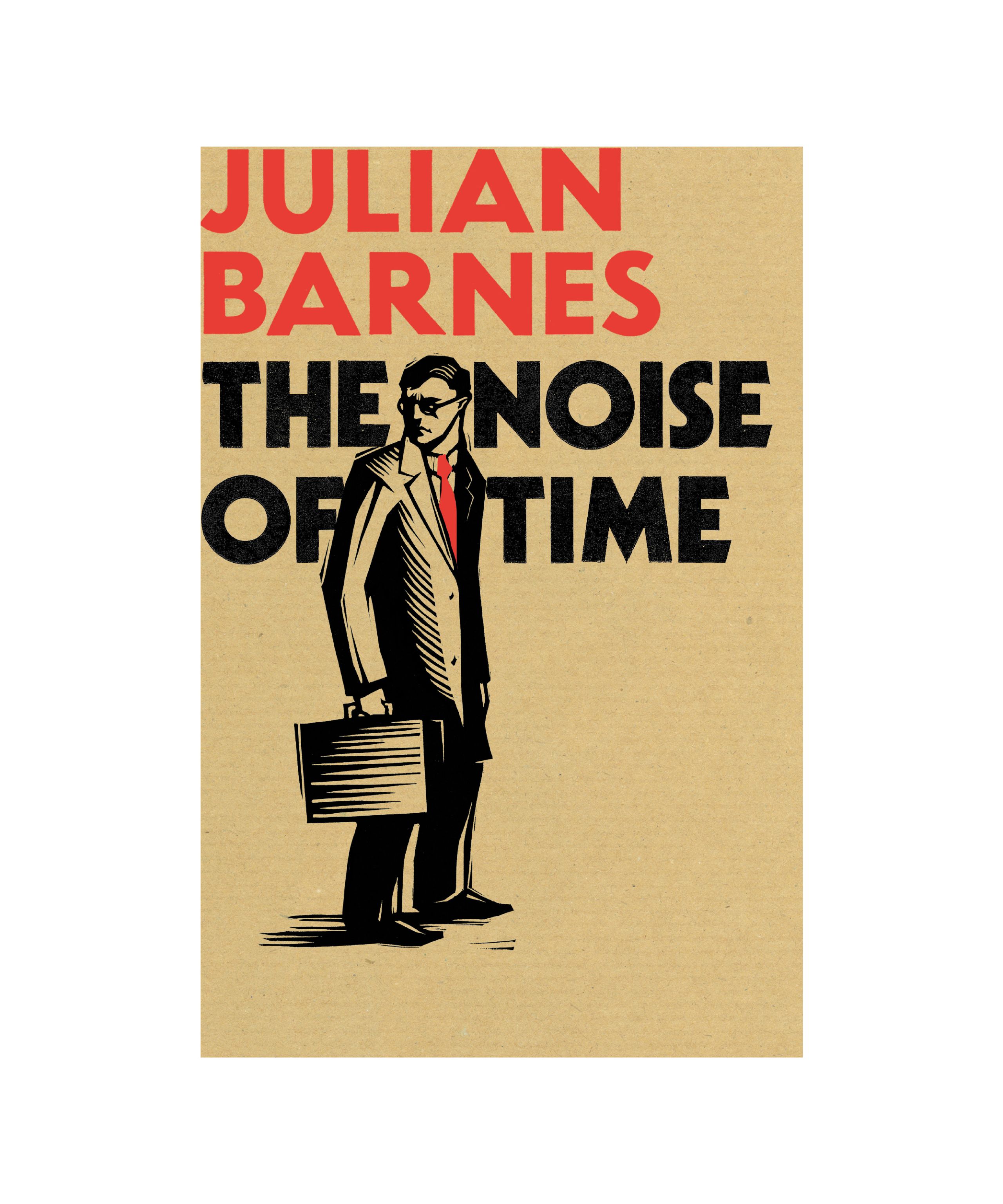

Books shouldn’t, of course, be judged by their cover, but no one can deny that the way a book looks can influence our feelings about it.

Designing a jacket for a book is not a simple matter of moving around some images and typing the author’s name and book title across the top. Rather, it involves meticulous research of everything from typefaces to patterns for wallpaper or clothing from a certain era, and sometimes multiple iterations of a cover before it is finalized.

Suzanne Dean is an award-winning designer and the Creative Director at Vintage, and has directed and designed dozens of book covers.

She has worked with the author Julian Barnes on the covers for his books for more than 20 years, and the two sat down to discuss what makes a good cover, and designing the jacket for Barnes’s The Noise of Time.

The first jacket Dean designed for Barnes was for Letters from London, a collection of the author’s journalism. At that time, Dean and Barnes had never met. Dean said: 'I read the text and came up with this idea of objects that had been sent through the post that represented different articles. I trudged round London, finding various things like a bowler hat, put stamps on them to make it look like they’d been sent through the post, and photographed them.'

It clearly worked, two decades later Dean and Barnes have worked together many times. In fact, the relationship between the pair is so fruitful that Barnes said: 'I do say to her on regular intervals, 'You’re not allowed to retire until I’ve stopped writing', and I mean it!'

You can read the full discussion between the pair, hosted by literary journalist Alex Clarke, here or listen to it as a podcast here.

How to create a campaign around a book

Brilliant books can sell themselves, but it helps to have a marketing and publicity campaign in place as well! When we talk about marketing we mean paid-for content such as adverts on social media or billboards at train stations, whereas publicity is ‘earned’, for example through press coverage. Here, Olivia Meade, Campaigns Manager at Penguin General, explains more about how to create a buzz around a book.

A marketing and publicity campaign is essentially all about telling people about a brilliant book. So, a campaign begins with the book – but does not end there. The book is merely the jumping-off point for us to work out all the ways we can bring it to the right attention in the right way.

The first thing to do is look at who the book’s audience is and all the different ways we can reach them. This involves sales and editorial too, whom publicity and marketing will work with incredibly closely. A publicity and marketing campaign is a crucial part of the publication and sales strategy, and we need to make sure everyone is on board with how we have decided to position the book in the market.

We publicists will have read the book cover to cover, sniffing out feature and interview angles, and looking at how it fits in with the wider world - thinking about pop culture and current affairs. For example, does it tie in with any emerging literary trends? Are there any upcoming anniversaries that work for the book? What is it saying about the current political moment? Is there a brand or charity we could look to partner with that links to the book? Alongside this we will be talking to the author, discussing how involved they would like to be in the campaign, what they are comfortable with, any ideas or contacts they may have, or personal angles they are willing to discuss.

Our collective marketing and publicity brains are whirring away strategising the campaign from the beginning. We look at all the possible avenues we have and, while a few remain the same for every book, not every campaign is the same. Working in publicity, you learn a lot on the job, including what media outlets impact sales, whether that be traditional (newspapers, magazines, radio) or digital (podcasts, the ‘influencer’ effect). This can vary hugely depending on the type of book! For instance, it is more unlikely for a debut novelist to be on BBC Breakfast than a famous face promoting a book. For the debut novelist, however, being picked for a prestigious slot like the Observer‘s New Faces in Fiction would be a fantastic coup. A book with a largely female readership will appeal to the literary editors of women’s glossy magazines (who are always such champions on social media too!), whereas harnessing the power of the brilliant online crime fiction community is key for a crime novel. They key thing is that a publicist tries all possible avenues open to them across national print and broadcast media.

For marketing, the same applies – so much is learnt on the job. As in publicity, there are many different avenues to go down to promote a book, so a marketer’s job is varied: from helping develop an author’s social media profile to designing proofs of books to send out to influencers and media to build a buzz around the book ahead of publication.

The difference between publicity and marketing is that the marketing strategy is dependent on how big budget marketers have to spend. They will look at who the audience is and how to reach them best, from the traditional, like train station billboards, to digital, e.g. social media advertising, all the while bringing out the messages of the book. I’m in awe of my marketing colleagues and the way they monitor, update and react to consumer behaviour, particularly online.

When marketing and publicity are working in harmonious tandem, campaigns zing with creativity, passion and excitement. Our ultimate aim is always to get brilliant books in front of, and hopefully in the hands of, readers who will love them as much as us.

We know that the process of writing and getting published isn’t always an easy one. We hope that this guide has given you both useful information and inspiration to keep writing and to navigate your next steps to getting published.

We wish you the very best of luck.

WriteNow is our programme to find, mentor and publish new writers from communities under-represented on the UK’s bookshelves.

It offers the chance to take part in free regional workshops, get personalised feedback on your work from an editor, and ultimately join our year-long mentoring programme.

Click here to find out more.

#MerkyBooks, our collaboration with grime artist Stormzy, is the home for a new generation of readers and writers including an annual New Writers’ Prize for young people. Follow us on Instagram to keep updated.

Further resources

If you want to know more about the publishing process, from writing through to publication, here’s some further reading, listening and viewing.

Books

On Writing by AL Kennedy (Vintage)

The author’s collection of blog posts and essays about the craft of writing, touching on topics including voice, writers’ health and research.

Writers’ and Artists’ Yearbook

This bestselling guide is updated each year, and as the definitive place to find a literary agent it includes contact details for more than 4,000 people in publishing.

Get Started in Writing Young Adult Fiction by Juliet Mushens

Literary agent Mushens covers everything from how YA fiction works to the big dos and don’ts of the genre.

On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King

One of the most famous books on writing, Stephen King’s tome can be found, well-thumbed, on the shelves of many authors and editors.

Eats, Shoots and Leaves by Lynne Truss (HarperCollins)

A humorous and useful guide to grammar and punctuation.

Podcasts

The Penguin Podcast

Guests on this podcast discuss how they write and where their ideas come from, and talk listeners through five objects that have provided inspiration for their work.

Acast | Apple Podcasts

The Vintage Podcast

This weekly books podcast includes book news, discussions and interviews with authors discussing their work.

Acast | Apple Podcasts

20 podcasts about writing that will have you penning a bestselling novel in no time - Bustle

14 podcasts every writer should listen to - Book Fox

20 inspiring writing podcasts to subscribe to right now - The Write Life

Blogs and videos

#Merky Books: How To Get Published: Watch this in-depth panel discussion about the publishing process between an author, literary agent, editor and publicist at the first ever #Merky Books New Writers’ Camp.

Abir Mukherjee: 10 Things I Learnt About the Publishing Process - Penguin.co.uk

Kit de Waal on why we need more diverse writers - Penguin.co.uk

Author Jane Corry shares her original covering letter - Penguin.co.uk

More posts about publishing can be found on Penguin.co.uk’s Getting Published blog.

See behind the scenes of publishing in Penguin's videos on printing, design and more on YouTube. See more of life at Penguin with our Work in Publishing videos.

Networks and organisations

Arts Council England offers financial support to individual writers who need time and space out of their day to day lives to progress their writing project.

Arvon is the UK’s home for creative writing, offering residential courses and retreats as well as mentoring opportunities. Grants are available for writers unable to afford course fees.

The Association of Authors’ Agents represents the interests of agents and authors, and a full list of its members can be found on its website.

The Good Literary Agency is a social enterprise supported by Penguin, which aims to discover, develop and launch the careers of writers of colour, disability, working class, LGBTQ+ and anyone who feels their story is not being told in the mainstream.

Pathways is a new two-year illustration programme, supported by Penguin, for talented and ambitious artists from diverse backgrounds who believe they can be the next generation of children’s illustrators.

The Society of Authors is the trade union for UK writers, and offers advice on contracts and more, as well as lobbies on the issues that affect authors.

Pen to Print provides a safe, collaborative environment for emerging writers in a number of genres including free workshops, competitions, events and through its new Write On! magazine, which aims to showcase emerging writers in print.

Regional writing organisations

Regional writing organisations are home to advice and information for new and established writers, and are a great resource if you want to find out about prizes for unpublished writers and local writing groups.

New Writing North - based in Newcastle, and supports writers in the North of England.

National Centre for Writing - based in Norwich, the National Centre for Writing was formerly known as Writing Centre Norwich, and covers the Eastern region of England.

New Writing South - based in Brighton, covering the South East region of England.

Spread the Word - based in London, and runs schemes including the Young People's Laureate for London.

Writing West Midlands - based in Birmingham, supporting writers across the West Midlands.

Writing East Midlands - based in Derby, supporting writers across the East Midlands.

Literature Works SW - based in Exeter and covering the South West region of England.

Commonword - based in Manchester.

Literature Wales - Literature Wales is the national company for the development of literature in Wales.

Scottish Book Trust - this is a national charity which promotes books, reading and writing.

Images of Sara Collins and Jane Corry by Justine Stoddart. Image of Claire Malcolm by Richard Kenworthy. Image of Madeleine Milburn by Libi Pedder.

Images of Sara Collins and Jane Corry by Justine Stoddart. Image of Claire Malcolm by Richard Kenworthy. Image of Madeleine Milburn by Libi Pedder.